On 25 January 1942, Colonel Hal George of the 5th Interceptor Command, the leader of the Bataan Air Force, was promoted to Brigadier General. On the one hand it was a great honor, and a recognition of his potential as a commander. On the other hand, the Bataan Air Force remained but a diminutive command.

On the same day, he coincidentally received a gift of information from Filipino sources, which reported a concentration of Japanese aircraft had assembled at the two airfields in the Manila area, Nielsen and Nichols.

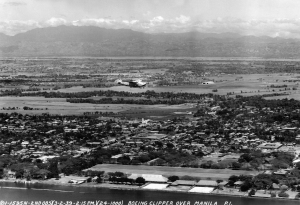

Nielsen Field was the former Manila Airport, which became a military airfield as war approached. It had been the headquarters of the Far East Air Force, the 5th Interceptor Command and related Air Warning Service, as well as the Philippine Air Depot. Today the airfield is no longer there, replaced by Makati City, Metro Manila, where the former runways form Paseo de Roxas and Ayala Avenue.

A Pan-Am Clipper flying boat is visible in foreground, and Nielsen Field is in the background to right in this 1939 view. (Courtesy Lougopal.com)

Nichols Field was five miles to the south, just outside Manila in the Parañaque area, and had served as a base for fighters as the war began. Since 1948 it has served as Manila International Airport with the co-located Villamor Air Base.

Nichols Field in a pre-war view. Note Manila Bay to right and much water in the lowlands surrounding Nichols. (Courtesy CVCRA.org)

But in January, 1942, the Japanese had occupied Manila and the two airfields. However, with this new information about the aircraft, Hal George now moved to give the Japanese at the two airfields a warm reception.

George had earlier secured permission from HQ USAFFE to make a surprise attack with his fighter aircraft when conditions permitted for obtaining a good result. He believed these conditions now presented themselves, aided by fair weather and a full moon which could support a night mission.

Six P-40s were readied for action the next day, and were loaded with .50-caliber machine gun ammunition and six 30-pound bombs each.

Armorers load small bombs beneath the wing of a 57th Fighter Group P-40 in North Africa during WWII. The P-40 could carry three small bombs beneath each wing giving it a modest ground attack capability. (Courtesy Warbirdinfomationexchange.org)

In the evening of 26 January, the plan went into the execution phase. Three P-40’s were to take off first, piloted by Jack Hall, Bill Baker and Bob Ibold, followed by the other three. At 2000 hours, the first aircraft took off, followed by the second. But the third was blinded by the dust from the first two, and cracked up on takeoff. The pilot survived but the aircraft was destroyed. As a result, the second flight of three aircraft did not take off.

The two pilots who safely took off circled around Corregidor Island to gain altitude before crossing over Manila Bay to Nielsen Field. As they approached Nielsen, the Japanese apparently thought the aircraft were their own and turned on landing lights and field lights to welcome them. The American pilots could hardly believe it, but wasted no time to attack, first dropping their bombs and then strafing the hapless Japanese. The attack finished up just as Japanese anti-aircraft guns become active and the two pilots returned safely to Bataan Field with reports of success.

Their reports encouraged General George, who ordered another attack by six aircraft. This time all aircraft made it off safely at 2300. Three headed for Nielsen and the other three for Nichols. The group bound for Nielsen, led by Ed Woolery, with Lloyd Stinson and Sam Grashio, did not have the benefit of any lights, and with Manila blacked out it took them some time to find the field before they attacked it again, with unknown results.

The other group, led by Dave Obert with Bill Baker and Earl Stone, successfully found Nichols and also an alert defense, which shot at them from the ground. Nonetheless, they bombed and strafed successfully, nearly colliding in the dark above the field as they did their work.

As a result, Obert left the area to avoid collision, and flew back across Manila Bay to search for some targets behind Japanese lines. He soon found them, and at about ten minutes past midnight managed to find and then strafe a column of 50 Japanese vehicles along a road with their light on, at least until Obert successfully made his pass along the column.

Obert then searched for another target, and began strafing again before his ammunition ran out. He then returned home safely, though he drew some fire from Fil-Am anti-aircraft units which did not expect a friendly aircraft from that direction – Obert wisely flew out over Manila Bay again and returned to Bataan Field, the last to land – all six pilots in the second attack successfully recovered at Bataan Field.

General George and his fighter pilots were elated at the success of the mission, even though it had cost one of the irreplaceable P-40’s in a takeoff accident. The Bataan Air Force had struck a blow at the Japanese, especially welcome after the difficulty Fil-Am forces experienced from Japanese airpower in the Abucay Line fighting of the previous two weeks.

The Japanese complained of air attacks killing women and children in Manila. They also sent Ki-30 ANN light bombers to attack Bataan Field the next day, without any significant result.

Filipino sources later reported the night air attack had destroyed 14 Japanese aircraft and killed 70 of the enemy. Information from Japanese sources indicated four aircraft attacked two times and inflicted no damage. To this day there doesn’t seem to be any final answer as to the result of this night air attack. But it likely that the American pilots hit something, especially on the first attack when Nielsen was lighted and they could see the field well.

It was a poignant reminder to the Japanese that the Fil-Am forces on Bataan were still capable of dishing out punishing blows against them, and that the campaign in the Philippines, and in Bataan would not be as easy for them as those in other parts of Asia such as Malaya or the Netherland East Indies. In fact, it would be quite costly to Imperial Japan, in terms of casualties, equipment, and their precious timetable for conquest.

References

Bartsch, William H. “Doomed at the Start: American Pursuit Pilots in the Philippines, 1941-1942.” Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 1992.

Pics from

Gen George HQ hut, at: http://lanbob.com/lanbob/H-19BG-extra/H-His/PI-AAC.htm

Pre-war Nielsen Field, at: http://www.lougopal.com/manila/?p=1463

Nichols Field, at: http://www.cvcra.org/interments/?menu=3&det=5030

P-40 loading bombs, at: http://www.warbirdinformationexchange.org/phpBB3/viewtopic.php?p=506867

Nielsen Tower is now a haven of world cuisine. http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/167201/makatis-landmark-nielson-tower-rps-first-gateway-to-the-world-now-a-haven-of-world-cuisine

It looks like a great place to eat, even better with the historical ambience!